Measuring distances on the internet is now child’s play: just type in two places, choose whether you want the results by road or by air, and you’re done. But how did it work in the 1850s?

How did a postmaster in the mid-19th century know the value of a stamp to put on a letter when there was no internet and not even the standardised system of quadruple rates?

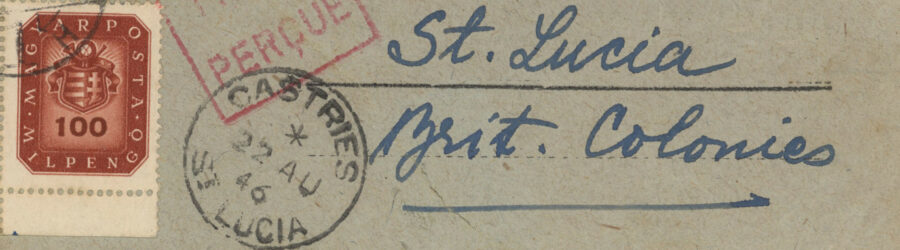

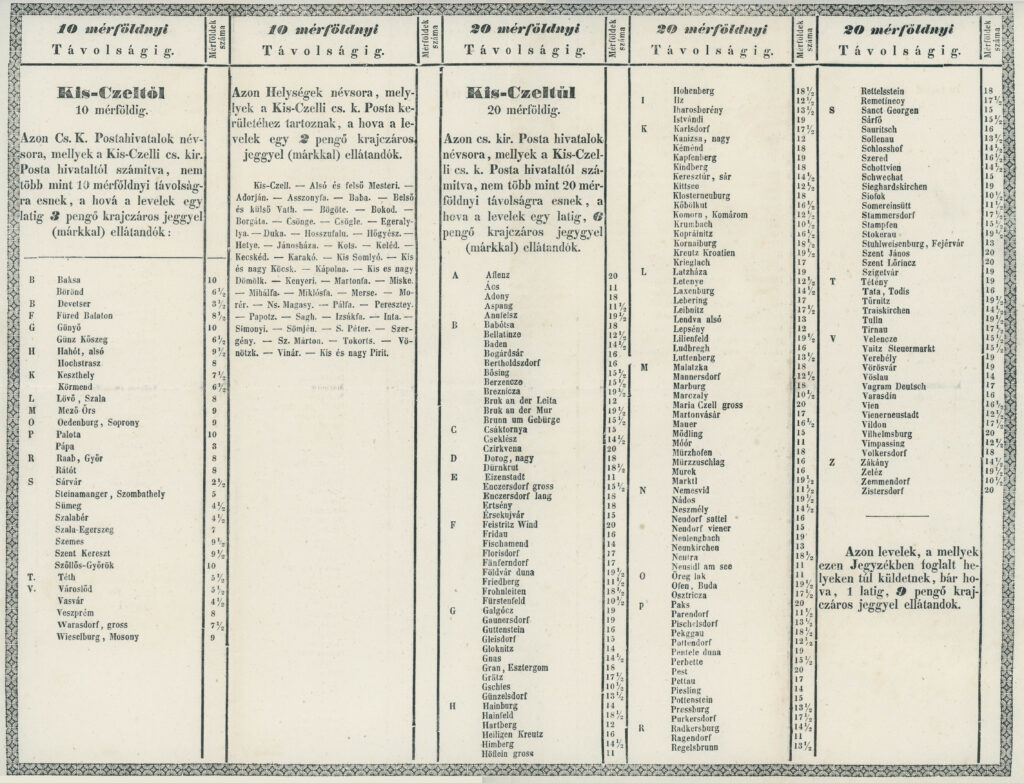

I recently found the answer to this question in an antique shop, where I came across an interesting table for the Kiscell post office, showing the rates for the area. The fact that such a wonderful piece of postal history has survived in the fine condition shown in the attached picture is truly remarkable, and I can only encourage fellow collectors not to forget antique shops and antique dealers among the sea of stamp shops and auction houses available on the internet.

The table shows four groups according to postal rates:

- Post offices within 10 miles: 3 krajcár.

- Post offices within 10 miles of the post office and belonging to the small postal district of Kiscell: 2 krajcár (local/suburban mail).

- Post offices between 10 and 20 miles away: 6 krajcár.

- For all other domestic letters, the rate is 9 krajcár.

The charges shown in the above rates are per lats, for heavier (multiple lats) items the above charges are of course a multiple of the basic charge in direct proportion. Until 31 December 1865, the weight of letters (domestic) was measured by the so-called Viennese lat, which was 1/32 of the Viennese pound, i.e. 1 lat = 17.5 grams. This was replaced by the customs pound / customs lat and then, from 1873 / 1874, by the kilogram / gram.

The table of charges must have survived from some time between 1850 and 1865, which can be deduced from the fact that the stamps appearing in the text of the table in 1850 are already mentioned. In the absence of further information, the end date is 1865, as the postal tariff was abolished on 15 November 1865.

The mile referred to in the text is the Austro-Hungarian postal mile, which is equal to 4000 Viennese fathoms. One Viennese fathom is 1,896 metres, so 1 postal mile = 7,5859 km.

It is worth recalling the concept of the delivery area (column 2 of the table):

- This refers to municipalities that did not have their own post office, and therefore belonged to a larger municipality in the area for delivery purposes.

- It was also called a suburb, and may be familiar from the term suburban express tariff.

- In any case, local rate letters sent to outlying areas are a rarity and are worth many times more than normal local mail. For example, a local rate letter sent to a suburb of Kiscell, say Baba or Adorján, would fetch a much higher price at auction than a local rate letter addressed and sent to Kiscell.

This meant that postmasters did not have to measure the distance when sending the mail, they simply had to find the municipality of the addressee using the table they received. This may be the reason why mail from this period is usually correctly franked by distance.

For those interested in the subject of postal distance calculation, I recommend the detailed study by Ferenc Orbán in Philatelica 1988/1, which can be downloaded free of charge from the MAFITT website.

The original article was published in the April 2022 issue of Bélyegvilág.